Calls for Ukraine

Calls for Europe

Calls for USA

A new study examining the long-term dynamics of transplanted stem cells in a patient’s body explains the effects of age on stem cell survival and immune diversity, making transplants safer and more successful.

For the first time, scientists have tracked what happens to stem cells decades after transplantation, lifting the veil on a procedure that has remained a mystery for more than 50 years. The findings could pave the way for new strategies in donor selection and successful transplantation, leading to safer and more effective transplants in the long run.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and their colleagues from the University of Zurich have been able to map the behavior of stem cells in the body of recipients for three decades after transplantation and gain insight into the long-term dynamics of these cells.

The study, published October 30 in the journal Nature, shows that in transplants from older donors, which are often less successful, ten times fewer vital stem cells survive. Some of the surviving cells also lose the ability to produce a number of blood cells essential for a strong immune system.

Each year, more than one million people worldwide are diagnosed with blood cancers, including leukemia and lymphoma, which can prevent a person’s immune system from working properly. Stem cell transplantation, also known as a bone marrow transplant, is often the only treatment option for these patients.

During the procedure, the patient’s damaged blood cells are replaced with healthy stem cells from a donor, which then rebuilds the patient’s entire blood and immune system.

Although transplantation can be life-saving, outcomes vary widely and many patients experience complications years later. The age of the donor is known to affect success rates, but what happens at the cellular level after transplantation has remained a black box until now.

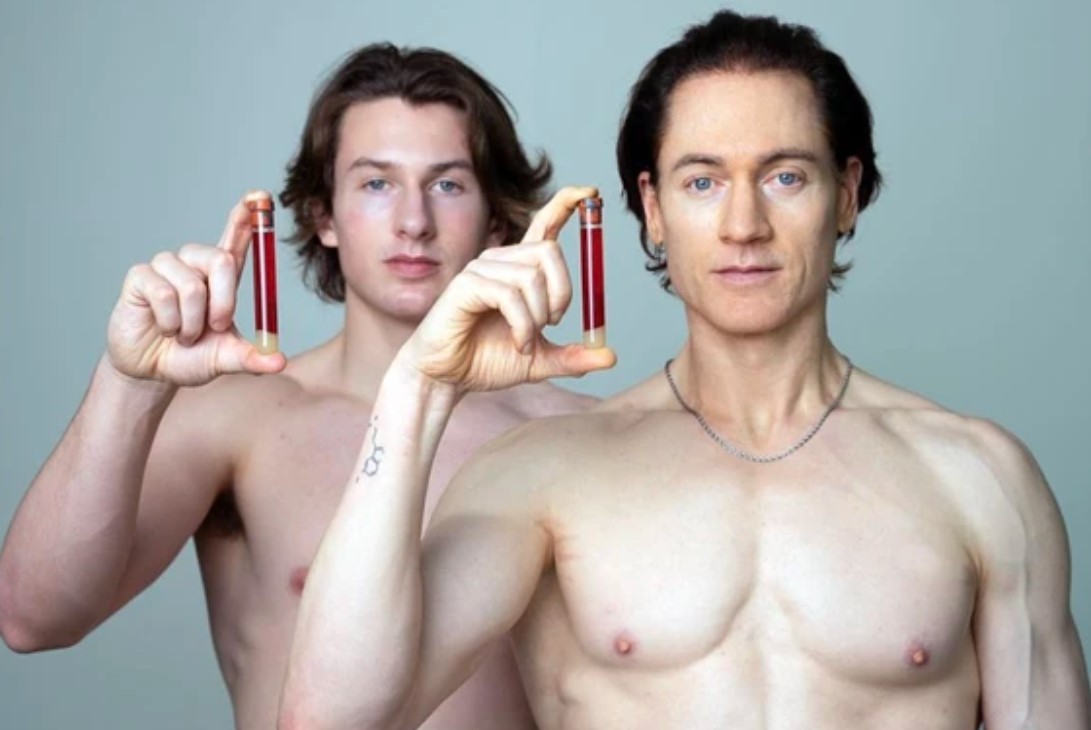

In the new study, scientists used advanced genome sequencing techniques to analyze blood samples from ten pairs of donors and recipients (who were siblings) for 31 years after transplantation.

By analyzing the mutations that occur over a lifetime in donor and recipient stem cells, they were able to track how many stem cells survived the transplant process and continued to produce new blood cells in the patient’s body, which was previously impossible.

The team found that for transplants from younger donors (ages 20-30), about 30,000 stem cells survived over the long term, compared to only 1-3,000 from older donors. This lower survival rate can lead to decreased immunity and increased risk of recurrence, which may explain why transplants from younger donors often have better outcomes.

Researchers also found that the transplant process causes recipients’ blood systems to age by about 10 to 15 years compared to matched donors, primarily due to less stem cell diversity.

Dr. Michael Spencer Chapman, study author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “When a person gets a transplant, it’s like starting their blood system from scratch, but what actually happens to these stem cells? Until now, we’ve only been able to inject the cells and then just monitor blood counts for signs of recovery. But in this study, we tracked decades of changes in one single sample, showing how some cell populations disappear and others dominate, shaping the patient’s blood over time. It was very interesting to understand this process in such detail.”

The study emphasizes that age is not just a number, but an important factor in transplant success. Although the hematopoietic stem cell system is remarkably stable over time, younger donors tend to supply a larger and more diverse set of stem cells, which may be critical to patients’ long-term recovery.

Please rate the work of MedTour