Calls for Ukraine

Calls for Europe

Calls for USA

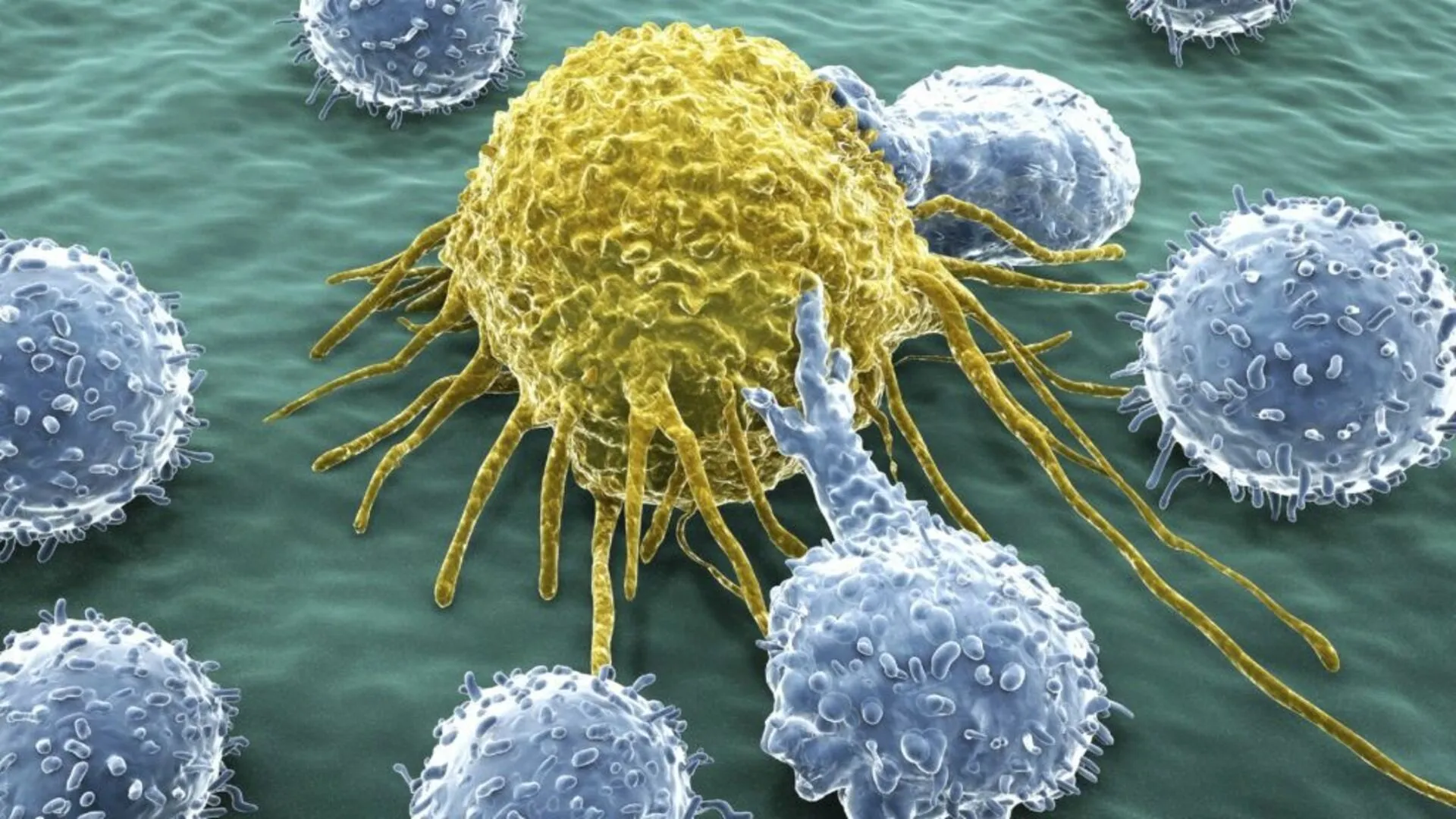

Japanese scientists have developed a new cancer therapy that can completely destroy tumors without involving the immune system. They used a unique combination of two bacteria — AUN, which has proven effective in experiments with immunodeficient mouse lines that mimic the condition of patients with weakened immunity due to chemotherapy. During the studies, tumors (including triple-negative breast cancer and human xenografts) completely disappeared within 240 hours after the introduction of bacteria, whereas traditional immunotherapy methods are ineffective in such cases. The study was published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

The history of using bacteria to treat cancer dates back to 1868, when German physician Wilhelm Busch described a case of tumor regression after unintentional infection of a patient. Later, in 1893, William Coley developed the first targeted bacterial therapy that stimulated the immune system to attack the tumor.

Modern immunotherapy methods — checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cells — are also based on activating the immune system. However, they are ineffective in patients with immunosuppression (suppressed immunity) caused by chemotherapy or radiotherapy, while such patients make up a significant proportion of cancer patients. In their new work, the team of specialists found a solution to this problem by studying the bacterial consortium AUN, previously isolated from mouse tumors. It consists of Proteus mirabilis (A-gyo) and photosynthetic Rhodopseudomonas palustris (UN-gyo), existing in a strict ratio of 3:97.

In experiments, the scientists administered AUN intravenously to mice with various types of tumors, including resistant breast cancer and transplanted human tumors (xenografts). For immunodeficient models, a two-step protocol was used: first, a low dose of AUN was administered, followed by a high dose 48 hours later. Control groups received saline. Safety was assessed using blood tests, histological samples, and cytokine level measurements.

The results allowed scientists to identify sustained tumor regression in all immunodeficient mice after administration of a double dose of AUN. Tumors, including human pancreatic cancer, disappeared completely within 240 hours without recurrence. The mechanism was found to be independent of immune cells: AUN selectively colonized tumors in which the ratio of A-gyo to UN-gyo bacteria shifted from 3:97 to 99:1, meaning that the UN-gyo population virtually disappeared in the tumor tissue, while A-gyo became the dominant species. Under the influence of cancer cell metabolites (fumaric and lactic acids), A-gyo transformed into filamentous cells that destroyed blood vessels. This caused selective intratumoral thrombosis (blockage of blood vessels by clots), necrosis (mass cell death), and hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells), which together led to rapid tumor death. Bacterial toxins, on the other hand, directly damaged cancer cells. At the same time, UN-gyo suppressed the pathogenicity of A-gyo: the level of interleukin-6 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines was significantly lower with two-stage administration than with single administration. This means that UN-gyo performed a protective function by reducing the inflammatory response while maintaining high antitumor efficacy through selective action on cancer cells.

This approach opens up new possibilities for immunocompromised patients, offering a long-awaited solution for cases where conventional immunotherapy is ineffective. “To accelerate the implementation of the results of this study in the social sphere, we are preparing to launch a start-up and plan to begin clinical trials within six years,” said Eijiro Miyako, lead author of the study from the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. “Right now, we are witnessing a new chapter in the history of bacterial cancer therapy, which dates back more than 150 years.” The new technique does not require genetic modification of bacteria and is effective against aggressive tumors. Future research may focus on evaluating long-term effects in large animals and determining the optimal dosage for humans.

Please rate the work of MedTour